One of the rewarding things about the science of quality improvement is how egalitarian it is. Anyone can play a role in making meaningful changes in systems around them, given the right tools and motivation. For example, have a cup of tea with a few octogenarians in rural Gateshead, UK, and they will proudly and proficiently describe the improvement work in their own community-led collaborative.

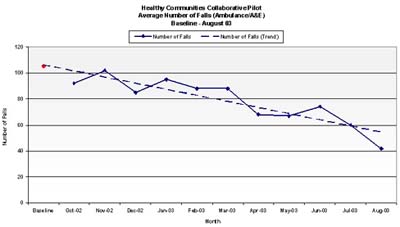

Their efforts have led to an impressive 32 percent reduction in falls among older citizens in their region — which translates into an annual savings of roughly £630,000 (US$1.45 million). And the improvement steps they used were as technical as making deals with local retailers for bulk orders of light bulbs, finding “handymen” volunteers to install them, and recruiting podiatrists and eye doctors to do screenings at a Saturday morning health fair.

Members of the Gateshead, UK, pilot team

share tea and strategies to reduce falls

Roots of a New Approach: A National Imperative

Reducing falls is part of a larger initiative in the UK known as the Healthy Communities Collaborative (HCC). The collaborative is taking an unusual but quite promising approach to health care needs: bringing improvement science into a community setting. The idea is to engage citizens as public health practitioners, in a sense, by training them to perform basic improvement techniques in their own neighborhoods to achieve measurable and sustainable change in specific health areas.

According to HCC Director, Linda Henry, the effort emerged in response to a National Health Services (NHS) resolution to address the country’s widening health inequalities. “The health of our poorer population is getting worse, and it is considered a serious trend that needs attention,” explains Henry. She adds: “The NHS has called on professionals to find creative ways to tackle the problem, to approach public health issues from a different angle; to build new partnerships and find hidden resources.”

The HCC has proven an encouraging test of this strategy. “It turns out,” says Henry, “that community members are very effective in running health initiatives themselves, especially in prevention. They’re often more successful than traditional public health programs, because local people are so strong in looking after health issues that impact their own neighborhoods.”

Organized and supported by the UK’s National Primary Care Development Team (NPDT), with evidence provided by the Health Development Agency, the HCC began in 2002. A panel of health experts and community members was convened to design the project as a collaborative, a change methodology originally developed in the US by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Through more than a decade of partnership with IHI, the NHS has successfully applied the collaborative approach in health programs from cancer to orthopedics, as well as a major initiative focused on primary care. The falls-reduction collaborative would go a step further — recruit and train ordinary citizens to lead their own collaboratives.

The decision to use this collaborative approach to reduce falls among older people reflected the scale of the problem. As Henry notes about falls: “People don’t really think about it, but it’s a hidden killer. There are 300,000 heart attacks a year in the UK, but four million falls.” The pain and suffering to patients and families, the resulting disability and mortality, can be devastating. And the humanitarian impact is compounded by the financial burden on the country’s health care system. Henry says that the cost to the NHS of hip fractures is more than £1.7 billion a year (US$3 billion).

Testing the Theories: The Pilot Phase

The HCC planning team defined the scope of a pilot project and identified practical changes to reduce falls in the context of community development. The concepts were both practical and humanitarian: reduce environmental risks such as faulty sidewalks and stairways, and also lessen isolation and engage residents and local organizations to get involved.

After a lengthy outreach campaign and application process, the group designed a one-year pilot and recruited three geographic areas to participate. Each one had five teams of 10 to 20 participants per team, comprising a mix of local citizens — interested retirees, business people, volunteer groups, and staff from local health agencies — with an average age of 70. NPDT project managers coordinated with local medical professionals to set up schedules for meetings and training sessions.

The goal of the collaborative was to reduce falls by 30 percent in each pilot site through simple interventions that were planned, implemented, and tracked by participants. By following the basic steps of the well-established Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Model for Improvement, the pilot teams practiced applying the specific change concepts in their own daily lives. Once a quarter, a core group representing each site met for two-day “learning workshops” with supporting professionals, to share data from the “action periods” in between and strategize on improving the change cycles.

The Right Ingredients: A Dose of Science Mixed with Community Spirit

The team partnered with housing and public works authorities to improve lighting, redesign doorways, and install shower grab rails; they convinced local businesses to sell bulk orders of no-slip bath mats, sturdy shoes, reading glasses and night lights; they involved podiatrists and optometrists in outreach campaigns — all of this systematically based on needs identified in surveys performed by the community group. The schemes they designed were both practical and creative. They included schoolchildren in the project by giving out pamphlets about falls and holding contest to design posters reminding their grandparents to walk carefully. They enlisted fitness instructors to offer Tai Chi classes to seniors. They publicized change principles through lunch groups, neighborhood meetings, on the local golf course, and so on.

Schoolchildren display their posters to help

reduce falls among their grandparents

By the end of the year the sites had achieved on average a 32 percent reduction in falls within their regions. More encouraging, the participants had implemented meaningful changes to sustain and spread the gains over time.

The NPDT’s Linda Henry says that seeing the accomplishments of average people, given modest training and professional support is truly inspiring. “What’s so exciting to me,” says Henry, “is how we’ve been able to galvanize public citizens to get involved, to take responsibility for dealing with a health problem. We just brought together people from the community and presented the evidence about falls to them. It was nothing new — basic, peer-reviewed data — but we made it relevant to them.”

“We told them that every five hours in the UK someone over 65 dies of a preventable fall. ‘In other words,’ we say, ‘while we’re meeting today, two people will die.’ That really energized people. It inspired them to want to help. They said: ‘That’s an incredible number. We must do something about falls.’ Then we taught them about PDSA cycles and the really simple and low-cost interventions that reduce falls. That’s all they needed to begin taking responsibility for improvement.”

The Path Ahead: Building on the Community Collaborative Approach

Based on the success of the HCC pilot, the collaborative is now in Wave II, with eight new regions participating in a trial through January 2005. In addition, the three Wave I teams are building on what they learned with falls reduction and have moved on to a new collaborative, “Widening Access to a Healthy Diet in Low-Income Populations.” Henry says that she is confident that the new focus will be just as effective in rallying public support because the issue has such clear public health implications. She says: “People realize that obesity is a huge problem caused by poor nutrition and lack of physical activity, and it’s getting worse — health professionals consider it a time bomb in the UK.”

Meanwhile, Henry says that NPDT’s directors from HCC are in discussions with the NHS about expanding HCC throughout the country and tackling other serious health problems such as diabetes and coronary heart disease. She says early indications are that NHS will adopt the community collaborative approach as a standard in national health campaigns.

While the opportunities to enhance the nation’s health are of primary importance, according to Henry the secondary rewards of this collaborative are priceless. She says, “It explodes all the myths about older people. When you show them a problem in their community and give them the right tools, they’re happy to be involved, to work toward a common goal. The project gave people a voice and the chance to make a difference, to gain a sense of purpose. It has released hidden assets in older people — demonstrating a hidden workforce out there. It’s a wonderful thing to be part of.”